The Burden That the Displaced Bear

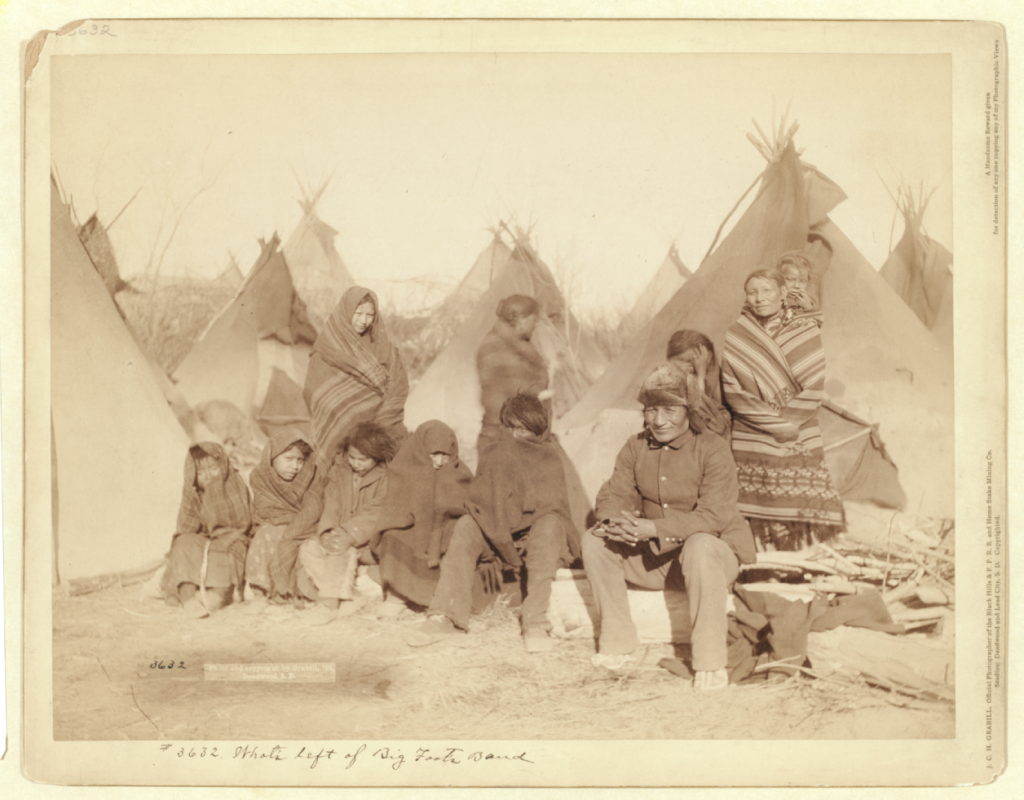

An 1891 photo of Lakota survivors of the Wounded Knee Massacre. A 2013 photo of the Za’atri camp for Syrian refugees in Jordan.

“War is hell.”

This phrase has become attached to U.S. Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman, a variation of something he reportedly said nearly 140 years ago to crowds in both Michigan and Ohio. Sherman himself gained fame as a conduit of that hell, a fact of which he seemed well aware. As the U.S. Army’s senior military officer following the American Civil War, he warned white Midwestern boys not to think that war bequeathed glory but instead to see its horror and cruelty as literal hell on earth.

In the years before and after that speech, Sherman oversaw the ongoing subjugation and displacement of many indigenous peoples from their homelands across the continent through the guise of war. Originating from hundreds of different Native nations, these people – whose homes, livelihoods, and cultures were devastated and upended – all experienced hell.

Many of them died, from disease or bullets. The survivors often were forced to resettle, sometimes far away from their ancestral lands. Their children were taken away to schools that further traumatized them and attempted to erase their cultural identities. Even today, while their descendants have demonstrated their resilience and will to survive, members of at least one of the 573 federally recognized American Indian/Alaska Native tribes continue to experience the effects of marginalization through systemic barriers such as economic inequality, health disparities, high rates of incarceration, and elevated mental health issues such as depression, substance abuse, and suicide – particularly among youth – as a result of trauma and toxic stress.

Sadly, stories of displacement – whether they occur within a country’s borders or push people outside them – are not uncommon. Forced migration is grim, and the trauma enacted within it can last for generations. Refugees, asylum-seekers, and others displaced from their beloved homes by war, violence, and terror are known to be at very high risk for mental health concerns, particularly post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

The light at the end of this very dark tunnel is that it’s never too late to start counteracting trauma, and researchers and health professionals always are seeking out evidence of the best care and treatment we can offer to those who have been highly exposed to trauma.

To accomplish that, however, we have to be aware of the depth of complexity in both the trauma experienced by and the cultural differences between various refugee groups and related populations. Understanding key concepts such as trauma load, postmigration stress, mental defeat, self-construal, and, of course, PTSD itself is paramount for effective treatment and healing.

TRAUMA LOAD

Trauma load or cumulative trauma refers to the amount and impact of traumatic events in a person’s life. For a refugee from a war-stricken land, this can and often does include the death and suffering of loved ones, torture, sexual and physical violence, threats of violence, food and water scarcity or deprivation, disruption to daily life including education and work, loss of home and belongings, and other horrific experiences that all but eliminate a sense of safety and security.

Even those lucky enough to escape the homes that became warzones may spend a decade or more in a refugee camp, with limited access to needs and care. And trauma doesn’t simply take a break while families wait in limbo for years.

As one might expect, greater trauma load has been linked to higher risk factors for PTSD, stronger symptoms, and worse health outcomes. Trauma load isn’t simply a stack of blocks weighing someone down, but a complex system of interlocking and interacting parts. Mental health care providers should be sensitive to treating unique aspects of different traumatic events as well as the connections between them.

Postmigration Stress

Postmigration stress is a phenomenon nearly all migrants – even privileged ones – deal with as they attempt to navigate new cultures and societal expectations, new languages or dialects, new schools and workplaces, and uncertain treatment and reception by their new neighbors and communities. For refugees and asylum-seekers, this stress can be further heightened by loss of control over their life choices, discrimination and mistrust, economic hardship, legal issues such as lack of citizenship status, and other concerns.

While treatment may not be able to remove the burdens placed by society on migrants, informed services can assist vulnerable populations through targeted coping mechanisms, empowerment to share their stories, and opportunities to find and build new, supportive communities.

Mental Defeat

Mental defeat is an important part of recent research into PTSD. It refers to the feelings of loss of identity, autonomy, dignity, and self in relation to significant, chronic pain. Targeting these feelings has become an important tool in treating physical chronic pain, and it is equally important to consider in treatment of psychological pain (recognizing, of course, that physical and psychological effects are never really separate).

However, some recent research has shown that mental defeat as a predictor of PTSD may not be consistent across cultures. Therefore, professionals treating PTSD should take individuals’ cultural variances into account and utilize creativity and adaptability in designing treatment plans.

Self-Construal

Self-construal is where cultural differences may most obviously manifest. The term encompasses a person’s identity in relation to the self in three parts:

- as an independent individual,

- as a member of a group or culture,

- and as a part of a close, interpersonal relationship with another person.

While Western cultures more often are identified with individualism and Eastern cultures with communalism, research into self-construal has demonstrated that these clearly are oversimplifications. Still, it is important to consider how identity may be closely linked to the effects of PTSD. A more individualistic person may view the pain of trauma as a part of their individual identity, seeing themselves as a victim and believing they were born to suffer. A person from a more communalistic background may see their struggles as an aberration from their communal identity, which could lead to feelings of failure, isolation, and marginalization.

These feelings certainly are not disconnected, but effective treatment will have to consider the different pathways of identity leading to and from a person’s experience of PTSD and related mental health concerns.

Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder

Finally, we come to the heart of the matter: what is PTSD and how does is manifest – particularly among refugees, asylum-seekers, and displaced migrants?

Before we dig in, it’s important to note that refugee experiences vary widely, and not everyone who has lived through trauma or has a high trauma load will develop PTSD. The risk is very real, however, and efforts to prevent, reduce, and treat PTSD and its symptoms can have wide-ranging and long-lasting positive effects, whether PTSD is ever diagnosed or not.

PTSD is the psychological effect that trauma often leaves imprinted on the brain and the body. It can reshape the brain, quite literally, toward a heightened, more intense, and more sudden fear response. Although we sometimes think of this response as irrational, we should understand it as a logical defense mechanism and survival tactic integrated into our psychobiology.

The problem is that our bodies suffer from this near-constant state of arousal and agitation. Chemicals released by toxic stress flood our brains, soaking them in fear, disconnection, and mistrust. Like all mental health problems, it interferes with our ability to enjoy life, our desire to seek out new experiences, our capacity to grow intimate and meaningful relationships, and our dignity.

Cultural Differences Present an Opportunity, Not a Barrier

For refugees and others highly exposed to trauma, PTSD can compound what we might consider normal, everyday stressors. A trip to the grocery store can become a nightmare of unfamiliar foods and customs. Paying a parking ticket is accentuated by the wilderness of a complex legal web and fears about citizenship status. Starting a new school may be accompanied by translation struggles, identity-based bullying, and making up for lost instruction time. Sudden, loud noises inadvertently may bring to mind gunfire, explosions, screams, and sirens.

Cultural differences should not be seen as a barrier to treatment, but as a strength to build resilience on and an opportunity for growth. Cultures form a major part of our identities, and PTSD eats away at our sense of self and safety. Enhancing the cultural foundation of a person suffering from PTSD can limit its effects and reverse the decay of identity. Everyone should have a self of place within their culture, within their relationships, and within themselves.

Sometimes that means we, as providers and neighbors, need to make space for people and their distinct cultures so that they can have a sense of place in which to thrive and grow. That could include educating ourselves in: cultural awareness and sensitivity; the backgrounds of and issues faced by the populations we serve, including immigrants and refugees; and how to build and grow communities around cultural identities to enhance education, job, and lifestyle opportunities rooted in specific cultures.

We need to continue to work together – clinicians, researchers, agencies, policymakers, and, above all, the communities themselves. We can and will avert many of the effects of trauma for our most vulnerable neighbors through sustained, open-minded, and evidence-informed efforts.

As social service agencies and behavioral health providers, our care and concern for families and children deeply affected by trauma – whether they are refugees, asylum-seekers, or displaced migrants – doesn’t stop at professional duty. Building healthier, empowered, and inclusive communities is our mission. Help us continue the journey toward a world that sees the suffering of one of us as a call to action for all of us.

Read more

Citations & References

Liddell, B. J., Cheung, J., Outhred, T., Das, P., Malhi, G. S., Felmingham, K. L., Nickerson, A., Den, M., Askovic, M., Coello, M., Aroche, J., & Bryant, R. A. (2019). Neural Correlates of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Symptoms, Trauma Exposure, and Postmigration Stress in Response to Fear Faces in Resettled Refugees. Clinical Psychological Science, 7(4), 811–825. doi.org/10.1177/2167702619841047

Bernardi, J., & Jobson, L. (2019). Investigating the Moderating Role of Culture on the Relationship Between Appraisals and Symptoms of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. Clinical Psychological Science, 7(5), 1000-1013. doi.org/10.1177/2167702619841886

Groen, S., Richters, A., Laban, C. J., van Busschbach, J. T., & Devillé, W. (2019). Cultural Identity Confusion and Psychopathology: A Mixed-Methods Study Among Refugees and Asylum Seekers in the Netherlands. The Journal of nervous and mental disease, 207(3), 162–170. doi.org/10.1097/NMD.0000000000000935

Wilker, S., Kleim, B., Geiling, A., Pfeiffer, A., Elbert, T., & Kolassa, I.T. (2017). Mental Defeat and Cumulative Trauma Experiences Predict Trauma-Related Psychopathology: Evidence From a Postconflict Population in Northern Uganda. Clinical Psychological Science, 5. doi.org/10.1177/2167702617719946

Kolassa, I.T., Kolassa, S., Ertl, V., Andreas Papassotiropoulos, A., & de Quervain, D. (2010). The Risk of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder After Trauma Depends on Traumatic Load and the Catechol-O-Methyltra nsferase Val 158 Met Polymorphism. Biological Psychiatry, 67(4), 304-308.

Jobson, L., & O’Kearney, R. (2008). Cultural differences in personal identity in post-traumatic stress disorder. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 47, 95-109.

Statistics & More Info

Find recent health statistics among American Indian/Alaska Natives from the Office of Minority Health, under the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Read the most recent edition (updated May 2019) of Tribal Nations and the United States: An Introduction, a publication developed by the National Congress of American Indians.

See the U.S. National Library of Medicine’s entry on the Wounded Knee Massacre from the exhibition “Native Voices: Native Peoples’ Concepts of Health and Illness.”

Read a brief historical summary about the trauma of Indian boarding schools from Northern Plains Reservation Aid, a program of Partnership With Native Americans.

See the most recent statistics (September 2019) on the Za’atri Refugee Camp for Syrian refugees in Jordan, from ReliefWeb, a digital service of the U.N. Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs. The camp has a population roughly the size of Parma, Ohio.

Find information on international refugees in Northeast Ohio from the Refugee Services Collaborative of Greater Cleveland, a group of Cleveland organizations and agencies serving refugees.

Read “Key facts about refugees to the U.S.” (October 2019) from the Pew Research Center.

Read the UNESCO’s description of displaced persons and displacement.